The Unlikely Saint and Reaction to his Martyrdom

Fr. Jerome A. Magat, SThD. is the vice-rector of St. Patrick's Seminary in Menlo Park, CA, where he also teaches moral theology and directs the Master of Divinity program.

Popular biographies of St. Lorenzo Ruiz refer to him as among “the most improbable of saints,” due to the unique circumstances that led to his martyrdom. This article will consider how Lorenzo ended up dying as a martyr, along with fifteen companions on September 27, 1637 in Nagasaki, Japan, as well as the reaction to his martyrdom when news reached Manila some three months later. This later dimension of the article reveals how so many in the Church have lost a sense for martyrdom as a form of glorification.

The "accidental" martyr

Lorenzo’s father was Chinese and his mother was Tagalog (native Filipino) and he received a first-rate Catholic education from the Dominicans in the Binondo section of Manila. A devout layman, Lorenzo, trained as a calligrapher, and also served as a lay catechist and a member of his parish’s Confraternity of the Holy Rosary at the Binondo Church (today, the Minor Basilica and National Shrine of San Lorenzo Ruiz), which is still a thriving Catholic community adjacent to Chinatown in modern-day Manila. Keep in mind that for over two centuries prior to the arrival of the Spanish (in the 1520's), Manila already had a thriving Chinese immigrant community, spurred on by trade. The arrival of industrious and zealous Dominicans from Spain initiated early missionary efforts, which eventually bore fruit, as evidenced by Lorenzo's family history.[1]

Lorenzo and his wife had a family of two sons and a daughter, all of whom were quite young when Lorenzo was falsely accused of the homicide of a Spanish colonial. In order to avoid arrest, Lorenzo planned to escape to either the port of Macao, adjacent to Hong Kong or to Formosa (now Taiwan) to hide, until the situation in Manila calmed down. Macao made sense: It was a city inhabited by many Chinese Catholics, who had been evangelized some eight decades earlier. Given Lorenzo’s Chinese and Catholic background, he could blend in quite easily.[2] So, on June 10, 1636, Lorenzo left his wife and three children behind to seek refuge abroad.

It was the Dominican priest, Fr. Domingo Gonzales, who arranged for Lorenzo’s passage, for what Lorenzo thought was a ship headed for Macao or Formosa. In reality, the ship that left the Philippines was headed on a missionary trip for Japan! However, the Dominicans never revealed this to Lorenzo prior to their departure, as they wanted to keep their plans extremely confidential (and perhaps dissuade Lorenzo from escaping Manila).[3]

In the preceding months, the Spanish civil authorities had prohibited missionary efforts to Japan, since many of them felt that these efforts threatened trade and diplomatic relations with the Japanese, who deeply opposed Catholicism.[4] And so, instead of landing in Macao or Formosa, the ship headed for Japan. It was not long before the group was arrested, upon landing in Okinawa. The group of sixteen was incarcerated for two years and eventually condemned to death during one of the more ferocious persecutions of the Faith there - a persecution that eventually wiped out the nearly 50,000 faithful who lived there![5]

A movement of grace (one that remains in the hidden counsels of God) must have occurred on the way there. There is no historical record that indicates that Lorenzo was ever told explicitly where the vessel was headed, but he eventually knew that their destination would certainly mean arrest and likely torture and death. It's quite accurate to describe him as the "accidental martyr" since his intent in seeking passage out of Manila never included missionary efforts! He was simply a fugitive. And yet, God had other plans. When Lorenzo and his companions landed at Okinawa, Lorenzo could have gone on to Formosa, but, he reported, “I decided to stay with the Fathers, because they (the Spaniards) would hang me in Formosa.”[6] Lorenzo was caught between attempting escape to Formosa and remaining with the missionary group. The circumstances surrounding his unexpected meeting with the Cross are noteworthy and the narrative is compelling: a fugitive on the run providentially ends up facing a martyrdom he never anticipated and his attempt to save his life (from arrest for murder) led to his martyrdom and gaining his life for all eternity.

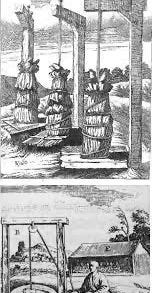

During his nearly two-year prison ordeal (one year in Okinawa and one year in Nagasaki) and eventual torture and execution, Lorenzo had multiple opportunities to denounce the Faith. The forms of torture were horrific: After huge quantities of water were forced down their throats, the prisoners were made to lie down. Long boards were placed on their stomachs and guards then stepped on the ends of the boards, forcing the water to spurt violently from mouth, nose and ears. Another form of torture included the insertion of bamboo needles under their fingernails.[7] During his interrogation and trial, Lorenzo felt his faith grow stronger. He exclaimed: Ego Catholicus sum et animo prompto paratoque pro Deo mortem obibo. Si mille vitas haberem, cunctas ei offerrem. ("I am a Catholic, and I shall die for God, and for Him I will give many thousands of lives if I had them.")[8]

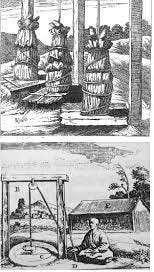

Eventually, five (including Lorenzo) of the prisoners were put to death by being hung upside down in deep pits. Boards fitted with semi-circular holes were fitted around their waists and stones tied to their bodies to increase pressure, as blood flowed to the brain. They were tightly bound, to slow circulation and prevent a speedy death. The martyrs hung upside down in agony for three days. The executioners always left one hand of the victim free so that they may signal their desire to recant, which could lead to their release. After three days, Lorenzo and another companion were dead. Still alive, three priests were then beheaded. Ruiz refused to renounce Christianity and died from blood loss and suffocation. His body was cremated, with the ashes thrown into the sea. Lorenzo and his fifteen companions (six lay persons and nine clergy) were beatified by St. John Paul II in 1981 in Manila (the first beatification held outside of Rome in Catholic history) and canonized by the same Pontiff in Rome on October 18, 1987.

It may be observed that many of us are accidental witnesses in the post-Christian society in which we find live. Perhaps born and raised Catholic, we may have never imagined having to give testimony to our Faith in such overt ways - especially in the face of increasing hostility from secularists. Even in the Philippines (which has a unique history among Asian missionary lands, as the only place where the Faith took firm hold without systemic persecution), post-Christian hostility to the faith has become much more vehement than pre-Christian aggression. Lorenzo and his companions serve as a bulwark of inspiration for those who did not necessarily expect to find themselves embroiled in contexts that now demand overt witness to the truth of the Gospel.

News of Martyrdom Reaches Manila

In the aftermath of the events of September, 1637, news of the martyrdoms first spread to Macao via the typical trade routes and eventually arrived in Manila two days after Christmas in 1637, three months after the event of the martyrdoms themselves. It should be noted that the martyrdom of Lorenzo and his companions was soon followed the martyrdom of the Jesuit priest, Fr. Marcelo Mastrilli, who died by the same method. Both events made deep impressions upon the native-Japanese Christians, as well as non-religious traders in the region. The events of both martyrdoms were immediately chronicled by civil and ecclesiastical authorities.[9]

Remarkably, the reaction in Manila was that of joy! The faithful gathered in the church of Santo Domingo and throughout the city and sang a solemn Te Deum, one of the most ancient songs of praise and thanksgiving to God - still sung on feasts, solemnities and Sunday’s when praying the Liturgy of the Hours. Clearly, Catholics in Manila were overjoyed that their own had been found worthy to die such a glorious death! The festivities over news of the martyrdoms were celebrated the entire day by the entire city, including all of the ecclesiastical authorities. Fidel Villarroel writes,

Soon the Jesuit and Dominican communities were notified, and, besides, the Dominicans received the priceless text of the narrative of the interpreters of Nagasaki. After the ecclesiastical and civil authorities were duly informed, the bells of San Ignacio, Santo Domingo and other churches of the capital started to ring merrily announcing the glad tidings of a victory, the triumph of Christian heroes. In no time all Manilans knew who the heroes were.[10]

This reaction is instructive, especially when Christians are being martyred in Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and many parts of Asia today. It is rare to hear Westerners (even within the Church) refer to martyrdoms as glorious. Instead, martyrdoms are often depicted simply as senseless acts of brutality or human rights / religious liberty violations. And while there remains a natural horror that one associates with such brutality, Christians in general and Catholics in particular are invited to see the transcendent meaning of such heroism.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church #2473 reminds us that the “martyr bears witness to Christ who died and rose, to whom he is united by charity. He bears witness to the truth of the faith and of Christian doctrine. He endures death through an act of fortitude.” So, contrary to contemporary opinion, the death of a martyr is far from senseless – it is the highest form of giving witness to Christ and the truth of the Faith. Moreover, history has shown that in almost every attempt to spread the Faith, persecutions and martyrdoms have been a part of the narrative.

In the case of the Philippines (that never had a prolonged persecution of Catholicism on its own turf), the only two canonized saints from that country died as martyrs overseas (Lorenzo Ruiz in Japan and Pedro Calungsod in Guam). Given the modern reaction to martyrdoms, it may be the case that many segments of the faithful today have lost a taste for this ultimate form of witness. Instead of singing the Te Deum in local parish churches, would the modern response be more of secular outrage? This is worth pondering.

If we believe in Divine Providence, Lorenzo Ruiz's martyrdom, in all of its paradoxical brutality andglory, was no coincidence. Grace won the day and buoyed him and his companions up to make the ultimate testament of love for the Lord, imitating his passion and death. May the reaction of Lorenzo's fellow-Catholics in Manila in 1637, rekindle in the Church a renewed devotion to the martyrs and inspire the faithful to see that this heroism in the modern era is truly glorious!

Lorenzo Ruiz and his companions were hung upside down in deep pits. Boards fitted with semi-circular holes were fitted around their waists and stones tied to their bodies to increase pressure, as blood flowed to the brain. They were tightly bound, to slow circulation and prevent a speedy death.

----

1 Fidel Villarroel, Lorenzo de Manila The Promartyr of the Philippines and His Companions (Manila: University of Santo Tomas Press, 1988), 1-11.

2 Villarroel, 56-64.

3 Villarroel, 57-58.

4 St. Francis Xavier, SJ's missionary efforts in the late 1540s had born much fruit at a time when the emperor's influence waned and the country was ruled by warring daimyos and the samurai nobility class. By the 1590's, there were nearly 300,000 converts, including a number of daimyos. The 1570s saw the rise of successive shoguns who at first were favorable to the Faith but later turned on the Catholics, leading to the promartyrdoms of Jesuit Paul Miki and his companions in 1597. With the arrival of Dutch traders (and their anti-Catholic influence on the shoguns) in the 1600s and the consolidation of power by Buddhist shoguns, persecution of the Church intensified, leading to the events that claimed the lives of Lorenzo and his companions (Villaroel, 25-33).

5 Villarroel, 65-70.

6 Villarroel, 68.

7 Villarroel, 88-91.

8 Villarroel, 103-109.

9 Villarroel, 123-130.

10 Villarroel, 130.